January 2007

Michael Brecker, 1949-2007

19/01/07 09:48

My first memory of the late, great saxophonist Michael Brecker, was at Catholic University's McDonough Arena in 1975, during his stint with the incredible drummer Billy Cobham. After an opening set by the soon-to-be-famous Hall and Oates, Cobham and his group, featuring trumpeter and brother Randy Brecker, guitarist John Abercrombie, trombonist Glenn Ferris, bassist Alex Blake and pianist Milcho Leviev took the stage. Needless to say, I was completely blown away. Cobham's albums with that line-up, "Crosswinds," "Total Eclipse," and "Shabazz," were some of the greatest jazz albums of it's time, and Michael Brecker's solo on Crosswind's "Heather" was such a moving performance, that it remains etched in my mind to this day. His fame increased along side his brother's in their "Brecker Brothers" groups of the '80, with Frank Zappa, and later with Steps Ahead. With Brecker's passing, the jazz world has clearly lost one of the greatest saxophonists it has ever known.

No saxophonist in jazz has had as pervasive an influence as Michael Brecker, since the death of John Coltrane in 1967. Across a wide range of stylistic backgrounds, Brecker developed the emotional intensity and technical dexterity of Coltrane’s mid-period playing into a highly distinctive individual style of his own, which was so widely imitated by aspiring saxophone students that Leeds College of Music took to nicknaming those teenage players who auditioned for its jazz course as “Ready-Breckers”.

In addition to leading his own bands, co-fronting the Brecker Brothers fusion band with his trumpet-playing brother Randy, and founding the groups Dreams and Steps Ahead, Brecker worked with such legendary jazz figures as the drummer Billy Cobham, and the pianists Horace Silver and Herbie Hancock. He was also one of the most prolific session players in history, contributing to more than 400 freelance dates by artists as varied as Paul Simon, James Taylor, Steely Dan, Dire Straits and Joni Mitchell.

From the early 1990s he worked most frequently with his own quartet, renowned for the way its members, the pianist Joey Calderazzo, bassist James Genus and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts matched Brecker’s energy. Yet he also undertook a major recording project of his own almost every year from 1987 onwards, and from 2002 found time to tour with Hancock’s tribute to the 1960s Miles Davis band, Directions In Jazz, which pitted Brecker against the formidable trumpeter Roy Hargrove.

Brecker was born in 1949 and grew up in Philadelphia, where he and his brother were taken by their father to see the likes of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington. Brecker studied the clarinet and alto saxophone, before transferring to the tenor instrument, which became his principal focus.

For the most part, despite owning an array of saxophones, he played an aged Selmer Mark 6, with which he became so familiar that he once said: “It’s as if I own every molecule of the instrument.” The degree to which he eventually became at one with the instrument was obvious in a sporadic series of unaccompanied solo concerts which began in 2001 with a recital at London’s Union Chapel as the opening of that year’s jazz festival. So accomplished was Brecker that he appeared to conjure an invisible band of backing musicians through the passing harmonic nuances and jumps between registers that he achieved within the broad sweep of his melodic lines.

Having studied at Indiana University, he followed his older brother Randy to New York, where in 1969 they joined Billy Cobham in the fusion band Dreams. Yet both brothers could not be typecast merely as jazz-rock players. In 1973-74 they became the horn section of Horace Silver’s quintet, playing soul jazz and hard bop at a level that matched any of Silver’s previous recruits.

On leaving Silver, after a brief return to Billy Cobham, Michael and Randy formed the Brecker Brothers, which made a series of successful albums for Arista between 1974 and 1981 that included the 1978 chart single East River. The band combined rock and soul rhythms with tightly written arrangements, and both brothers had plenty of opportunities for extended solo playing. The formula was successful, but the band ceased touring in 1979 and broke up in 1981, although it reformed briefly several times in the 1990s, finally touring as a conventional acoustic jazz group, and reinventing a high percentage of its original repertoire for this new format. During the 1970s the brothers also owned the New York jazz club Seventh Avenue South, where they played frequently.

In the meantime, Brecker formed Steps, with the vibes player Mike Mainieri, a group which in its second incarnation, Steps Ahead, brought a high level of instrumental virtuosity to a repertoire that tightened aspects of the Brecker Brothers sound into what became a universal paradigm for 1980s rock fusion.

Outstanding instrumentalists who worked with the band included the guitarist Mike Stern, the pianist Don Grolnick and bassists Eddie Gomez and Darryl Jones. Brecker led the group for the latter part of the 1980s, but in 1987 he cut the Michael Brecker album for Impulse, which effectively launched the solo recording career that became his main interest. On this album he used the Electronic Wind Instrument which allowed him to convert his formidable saxophone technique into input for a synthesiser.

Brecker’s subsequent discs include Tales From the Hudson, Two Blocks From the Edge, and Time is of the Essence, plus a ballad collection, The Nearness of You on which he was joined by Pat Metheny and Herbie Hancock, with James Taylor making a guest appearance in return for Brecker’s numerous cameos on the singer’s discs. He won eight Grammies, and he achieved the unique double of winning both best instrumental performance and best instrumental solo in two successive years.

In the summer of 2005, Brecker was found to have MDS (myelodysplastic syndrome), cancelling all his concerts, and undergoing an extended course of chemotherapy. Despite his illness, which later developed into leukaemia, he recorded a final album, completing it two weeks ago. He is survived by his wife, Susan, and their two children. He will be greatly missed.

SoundExchange: Tracking Down Artists for Royalties

05/01/07 09:46

In July of 2005, I wrote about Neeta Ragoowansi, a fabulous singer, musician, and a former entertainment attorney for the Kennedy Center. Neeta continues to use her powers for good, working as the Membership Director of SoundExchange, a nonprofit agency based in Washington, D.C. and authorized by the U.S. Copyright Office to collect royalties from digital broadcasters and pay them directly to performing artists. Founded in 2000 and initially part of the Recording Industry Association of America, SoundExchange made its first payments in 2001 and, after a slow beginning, has begun to double its annual collections. Recently, SoundExchange had come under fire for not doing enough to find those musicians, and see to it they get what they derserve. Those detractors couldn't be more wrong, as the Bakersfield Californian's Robert Price found out. Sound Exchange continues to find artists and their families, and for those that can't be found, their royalties reside in a general fund, to support their fellow deserving artists. In Price's December column, he detailed just how difficult it can be for Sound Exchange to find these artists, and how rewarding it can be when they do.

In a recent blogs, SoundExchange was taken to task for not doing enough to get royalties for artists like, T. Bone Burnett, Ton-Loc, Flock of Seagulls. As Neeta explained to me in a phone conversation last week, "That at the time of their release, any unclaimed funds would go towards SoundExchange's operating costs, thereby lowering the administrative fee charged. This would, then, in turn result in a larger payment being made to the featured artists and sound recording copyright owners who are paid by SoundExchange. There have been some artists who, upon hearing this explanation, chose not to claim their funds and opted instead to have their payments in essence redistributed among other featured artist and sound recording copyright owner payees in this manner." A noble way of giving back in the music world if ever there was one.

Last December, Price wrote: "Before 1995, U.S. recording artists weren't entitled to airplay royalties of any sort. The Digital Performance in Sound Recordings Act of 1995 and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 changed that -- at least for Internet and satellite radio.

The nonprofit organization SoundExchange, authorized by the U.S. Copyright Office to collect and distribute royaltiesassociated with those specific media, started with a royalty pool of $5.2 million. About 90 percent of that money has been distributed to thousands of artists worldwide. Of the 9,000 performers identified as eligible in September, the group has located about 2,000. The rest are owed $500,000.

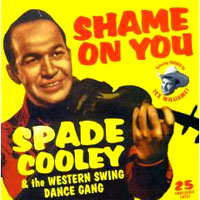

"This is just in its infancy and it's expanding every year," said Holland, a former reporter for the music industry weekly Billboard who does contract detective work for SoundExchange. Finding beneficiaries can be tough, though. Take Cooley, the legendary World War II-era Western Swing bandleader and '50s television host who murdered his wife at their Mojave ranch in April 1961.

Cooley suffered a fatal heart attack in 1969 while on a furlough from prison -- three months before he was to have been paroled. He left behind a catalogue of up-tempo hits and three children -- Melody, born in 1946; Donnell Jr., born in 1948; and John, a son from his first marriage, born about 1935.

The star witness against Cooley was his 14-year-old daughter Melody, who witnessed her mother's fatal beating. "She would be about 60 today," said John Simson, executive director of SoundExchange. "We'd like to talk to her." He'd like to talk to her brothers too.

Before Simson gives up, he might want to ask actor Dennis Quaid, who's planning to tell the Spade Cooley story one day with a film called "Shame on You," after Cooley's biggest hit. Quaid purchased rights to the stories of Cooley's children. Simson counts on people like Holland to do most of the legwork.

"Best job I've ever had," Holland said. "So many of these so-called heritage artists are just off the radar. They're people who still get airplay on super-hip satellite stations but not so much anywhere else. And most of the time they have no idea they're owed any money." He remembers fondly the day he tracked down the widow of Ernie K-Doe, a New Orleans R&B singer who recorded the Allen Toussaint song "Mother-in-Law."

"I've got a couple thousand dollars for your late husband," Holland told Antoinette Fox, who'd been yelling at a delivery man in the kitchen of the Mother-in-Law Lounge when he called. "Child, you just put the Thanksgiving turkey on the table," she replied. Word of mouth is Holland's best tool. It has worked elsewhere -- most recently in Shreveport, La., another country music hotbed.

It might start here with Red Simpson, who is best known for his country songwriting prowess but also had moderate success as a recording artist during the late-'60s/early-'70s heyday of the truck-drivin' genre -- none better than 1971's "(Hello) I'm a Truck." "The guy told me they've got eight-hundred-and-something (dollars) for me," Simpson said. "What a great deal. 'Course my wife will probably get it."

The efforts of Holland, Ragoowansi, Simson and others on behalf of these performers continues, and in this ever growing electronic age of mp3 downloads, webcasts, streaming audio, the murky history of the recording industry and the struggling independent labels, SoundExchange continues to be a welcome ally to performers and artists all over the world. You can visit SoundExchange at http://www.soundexchange.com. You never know, they just may have some royalties for you.